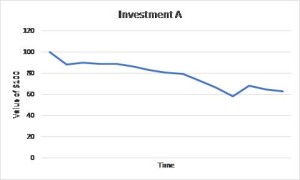

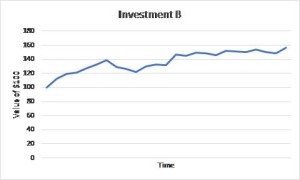

As we discuss in our investment tenets, one of our beliefs is that volatility is a necessary evil to produce returns. Consider the two investments choices below. Which one would you invest in?

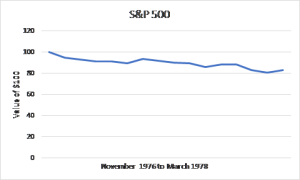

Most people would of course pick Investment B attracted by the 60% return over time as opposed to a loss of 40% in investment A. In fact, both the above graphs are the returns of the S&P 500, but at different times. Investment A is the S&P 500 between October 1973 and November 1974 and Investment B is between December 1974 and November 1976. If you had invested in the S&P 500 in November 1976 encouraged by the run up, you would have gone on to lose about 20% over the next year and a half as seen below. (Which brings us to our other belief which is to never chase returns- that is a topic for another article).

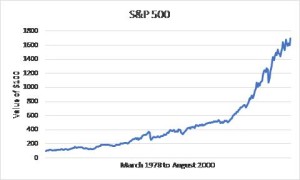

The reason we picked that period is because of what happened subsequently. The S&P 500 went on to increase 18-fold over the next 20 odd years to August 2000 as seen in the chart on the right below. Along the way, it had several drawdowns including a crash of over 22% in one day on October 19, 1987. It is this volatility that earns stocks a higher return than bonds. In investment parlance, this is called the risk premium. (Please note, for this analysis we have used the S&P 500 price returns for illustration purposes as the data for the total returns, i.e price returns plus dividends is not readily available for older time periods)

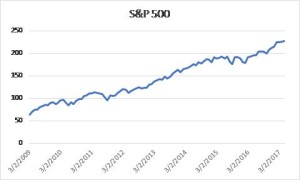

A similar thing happened more recently as seen in the charts below. (Here we used the S&P 500 total returns) On the left is the chart of the S&P 500 from January 2000 when the internet bubble burst, to March 2009 at the bottom of the market during the credit crisis. An investor invested in the S&P 500 would have been frustrated by a loss of 40% after almost a decade. If he were to sell at that point, he would have missed the subsequent bull market that more than doubled the original investment (almost four times from the bottom in 2009)

A final note: The above analysis will no doubt tempt a few readers to question why an investor could not sell at the top of the market in 1999 and then buy again at the bottom in 2009. That is called market timing, which is impossible and attempts to do that have been detrimental to investor’s returns. As they say, nobody rings a bell at the top or the bottom of the market. (Another belief of our investment tenets and a topic for a different article)